“Do they have cars in Pakistan?”

The question clung to the tater tot infused air of the middle school cafeteria.

I stopped munching on my bologna and white bread sandwich so I could properly gawk at the girl who had asked such a preposterous question. A look passed over my face that you might imagine wearing yourself if some 14-year old on the other side of the world asked you if they have clouds in America.

It was kind of her to ask, really, about the country where my American parents had taken me while still in utero, to be born and to grow up as neither American nor Pakistani. She was making a monumental effort to connect to a strange person, and for that, with all the struggling maturity of my adulthood, I applaud her.

But as a teenager, my brain couldn’t wrap itself around this equally monumental lack of basic education. I wondered if she didn’t also imagine me living in a tent and riding a camel to school every day.

Of course, this was pre-9/11, before anyone in the West cared anything about any country ending in -STAN, before Newsweek declared Pakistan the world’s most dangerous country.

I eventually closed my gaping mouth and in a very graceless way told her, “Yes, they do have cars in Pakistan.”

Actually, I probably said something more like, “D’uuuh” with an aggrieved roll of my eyes. We were in eighth grade after all.

From then on I stopped trying to tell people about Pakistan, although it was the only thing I really knew anything about. Despite looking like an American descended straight from Germany, it was Pakistan that was my home and my world. I couldn’t understand this strange all-American culture where kids went to summer camp and listened to Britney Spears but didn’t study geography.

I slowly receded into myself and went quiet, in the same way the hum of our house in Pakistan would suddenly die whenever the government cut off the power. By the end of the school year, when everyone passed around their yearbooks for everyone else to write nice things in, the nicest thing anyone could write in mine was how nice I was.

Oh, and of course the ever-convenient “HAGS” in case I needed any more proof that no one actually knew who I was.

Since then, I’ve spent exactly one adolescence and one young adulthood trying to sweep my past as a hyper-traveled Third Culture Kid under the carpet and then trying to find myself again in that same lost identity.

I still get strange looks and blank stares when people ask where I grew up. But (mostly) I forgive them for that. It is outside their context, beyond any frame of reference they might have when a white, blond girl says she’s from Pakistan.

But I’ve discovered one thing that helps connect the dots and creates a sprinkling of context.

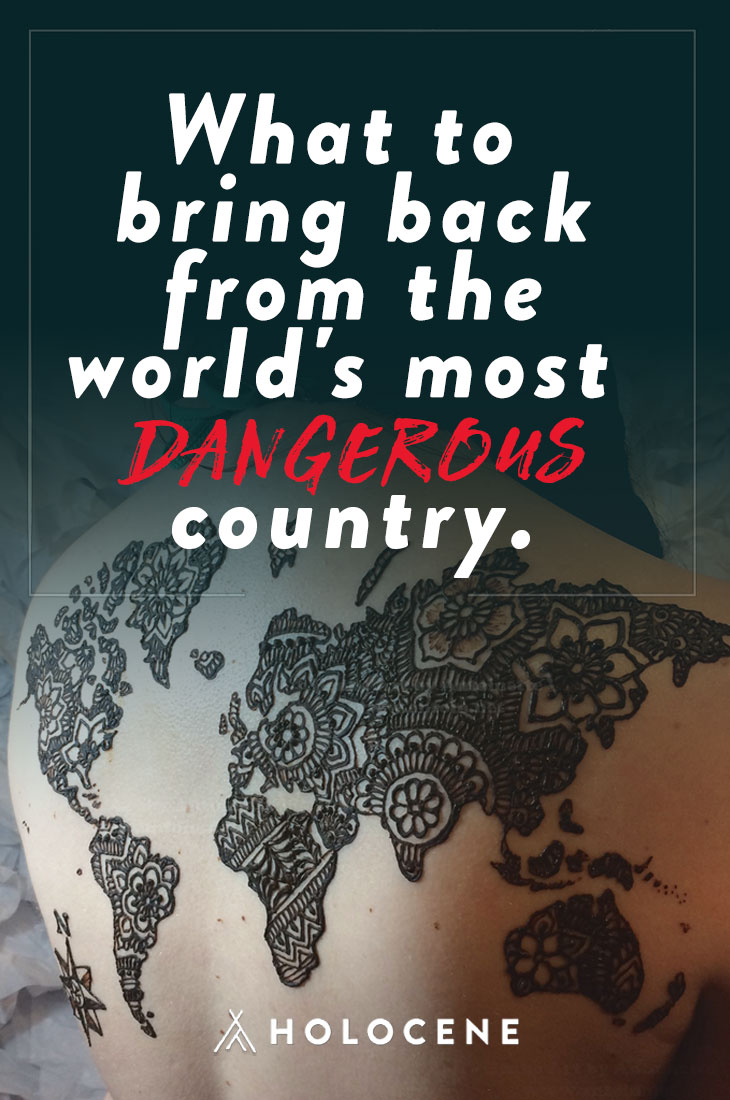

Thanks to the proliferation of henna tattoos at fairs and carnivals and mehndi coloring books for the stressed out child within, my own skill at this South Asian art form has become a useful ticket for entering American circles with something to give and a bridge to connect.

Thanks to the proliferation of henna tattoos at fairs and carnivals and mehndi coloring books for the stressed out child within, my own skill at this South Asian art form has become a useful ticket for entering American circles with something to give and a bridge to connect.

And so, half a lifetime after rolling my eyes to the rhythm of ignorant questions in the cafeteria, I find myself bending over a stranger’s foot, my nose hovering inches above her painted toes.

Mid-winter sunlight is streaming through my hair as it falls in a curtain over my canvas. With one hand I steady the pale, cool skin, and with the other I draw a line of rich, brown henna into a small diamond just below her pink polish. I connect the diamond to another and yet another diamond down the length of her toe until the henna erupts in a firework of swirls climbing up the top of her foot where it kisses the bone of her ankle.

Pleasantly surprised at my ability to draw more than a squiggle or two, the four women around my friend’s kitchen table begin to ask me questions.

I forget the cone of henna in my hands for a moment as I look up and find my long-lost voice. It begins to tell scraps of my story, about growing up in a boarding school nestled in the Himalayas, of buying my first mehndi as a 12-year old, and how this rite of passage shopping in the bazaar with my head dutifully covered brought me all the way to today, to an all-American henna party in the middle of Indiana.

For the travelers of the world, for those who come and go more than most, we can’t always get the non-travelers to understand or to see us for who we are or who we become out there on the road. Bits of other countries and cultures and languages cling to us as we pass through, as if we become magnets attracting curly scraps of precious metals along our way. The force of this experience is so strong that when we come home, or to the place we once called home, we find we can’t shake off these bits of other places, that they have become part of us.

It can be so lonely and so isolating when we can’t make those connections that we crave because of all the jangly pieces from other places we carry around our necks. But it’s our fault alone if we don’t try. And instead of tugging at the skirts of our social media followers, begging them to be amazed at our adventures in a modern day version of the old vacation slides no one actually wanted to see, perhaps we reach out and make a real connection.

It can be so lonely and so isolating when we can’t make those connections that we crave because of all the jangly pieces from other places we carry around our necks. But it’s our fault alone if we don’t try. And instead of tugging at the skirts of our social media followers, begging them to be amazed at our adventures in a modern day version of the old vacation slides no one actually wanted to see, perhaps we reach out and make a real connection.

When I came home from four months in Italy, I brought with me packets of Italian hot chocolate. I cooked them over the stove with a tiny bit of milk and a lot of whipped cream, and I shared them with my family at Christmas time so they could taste a small fragment of what it was like for me to fall in love with Italy. They’ll never fully know of course. But at least they had a taste.

And now 17 years after my family left Pakistan, the only way to get people to see past my American exterior to the strange blood of the mixed-culture mutt inside me is to create.

Creativity, after all, is the best souvenir. Sprouting from within you like a vine, its twisting stems become extensions of yourself, with one hand grasping at the roots of some place or identity and the other reaching out to offer the experience to others. To offer yourself to others.

Creativity, after all, is the best souvenir. Sprouting from within you like a vine, its twisting stems become extensions of yourself, with one hand grasping at the roots of some place or identity and the other reaching out to offer the experience to others. To offer yourself to others.

“Creativity, after all, is the best souvenir.”

Somehow all the other souvenirs you collect along the way – the leather bracelets from Florence, the pashmina scarves from Kashmir – don’t have the same effect.

So instead of passing out trinkets from my travels, I have a friend who invites her friends, and I make chai for them the Pakistani way, and we sit around the kitchen table drinking it as I pull out my henna. And then I touch these people, skin to actual skin, and I turn their bodies into art.

And then maybe, just maybe, they see a sliver of who I am as a traveler, and maybe, just maybe, I find myself feeling whole and alive and connected again. My roots touching their branches, no longer invisible, no longer that kid in the cafeteria that no one understands.

When one of the women gets up to leave, her face shining with smiles, she waves her arm, bedazzled with henna from wrist to elbow, triumphantly in the air. “I love it,” she says. “I can’t wait to show everyone at work!”

I find my pride in her pride and smile too, the smile of the creative who has created something worthwhile out of the depths of me. I imagine those vines of creativity wrapping themselves around us, connecting us with their delicate fingers, like diamonds of henna touching and twisting and turning into something beautiful.

Henna and photo by Antoinette. See her work at @antoindotnet